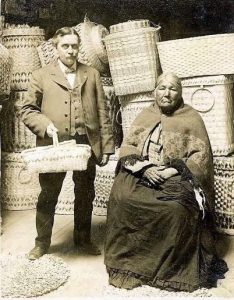

Amos and his Ice Wagon – Courtesy Omena Historical Society.

“Please find enclosed one weather-beaten old shoe. The shoe was removed from Bodie (a Ghost Town) during the month of August 1978… My trail of misfortune is so long and depressing it cannot be listed here.” said one person, returning the old shoe.

A younger correspondent blames getting grounded by his parents on the ghost town curse. Another child simply writes: “Sorry I took the glass pieces. I thought they were pretty. My fish died the day after.”

The Agosa (sometimes spelled Aghosa, more about that later) marker in the cemetery behind the Omena Presbyterian Church

And then there is this, “So sorry for picking these up. I love antiques and being a Christian I felt so guilty for taking these on Monday. Not to mention Tuesday we got a flat tire and my husband hit his head on a rock.”

There are ghost towns everywhere, now deserted, that some people believe can bring misfortune. And the fact that this belief endures says a lot about our desire to believe in the otherworldly in places like this. Or perhaps just the power of a guilty conscience. Items taken from these spots bring bad luck to the takers, it is said. They return them, with hopes that their luck will change.

Omena has two ghost towns near enough to give us pause

Aghosatown to the north, and Manseau’s Mill to the south. Is there a curse that brings misfortune to those who misuse this sacred space?

All around the Omena area, nature provided an abundance of food items that were free. Wild strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries were available for the picking. There was water swarming with bass, whitefish and lake trout, pike, and sturgeon. Small game and birds, especially passenger pigeons, were easy targets. And on Sundays, they had the Mission Church on the hill. It seems as though Ahgosatown Indians should have been living in paradise. But that was never the case.

In Aghosatown houses women had to push past the tragedies, loosing children and husbands to smallpox and other diseases, caring for children while making baskets to sell, in houses while newspapers covered the walls to keep out the cold winter winds. There is a memory in the OHS archives of a time quite late at night when there was a knock at the door. The father opened it, one of the Ahgosatown Indians stood outside with newly finished baskets. He explained that his family had no money for food so had worked to finish the baskets that night in hopes that they could exchange them for something to eat. He had come to one of the white friends they could count on for help, not for a free handout, for an exchange.

A ghost town was born

The Indians owned their own land here. Wouldn’t that be an advantage? Perhaps, but owning their own land usually meant that it had to be cleared and made ready before any farming operation could take place. This was a tremendous job that required proper tools and often a lot of backbreaking work. At the same time, the early lumber camps were hiring them to harvest timber, also hard and dangerous work. But by the early 1900’s lumbering had largely ended in Leelanau County and Ahgosa’s people fell back on their farms for their existence.

They quickly found that their farms, small plots many of them only forty acres or less, were unable to sustain them in the cash economy. Young people began to leave for the cities where manufacturing jobs could be found. Some of those who stayed found seasonal work on area farms, some found work in town making deliveries. During the depression years of the 1920s and 1930s work was so scarce that many of the Ahgosatown families ended up having to sell their farms and move away.

Manseau Mill

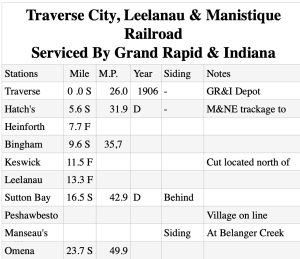

South of Omena at the hump in the road where Belanger Pond now sits serenely off to the side, stand the remains of an old mill, once called Manseau Mill. It once had its own railroad siding on the old Traverse City to Northport Railroad route, and was a gathering place for Leelanau County farmers, who brought their grain to the grist mill for sale or to be ground for their own use. Not a real town, but as a stop for the train, it was listed right along with the other towns on their schedule.

The water-powered mill there was built in 1859 by Antoine Manseau on what he named Kenosha Creek after an Indian named Keywatosa. He dammed the creek, built the 26-by-30-foot mill, and started grinding grain with a pair of imported millstones. It probably was the oldest grist mill in the Grand Traverse area.

The mill has new owners

Maude the Train’s Schedule. Right next to Omena (at the bottom) is the Manseau Mill stop in 1906. It is not the only Ghost Town on this list today.

In 1906, the mill was bought and operated by Eugene Belanger and sons Ignatius, Alexis, Luke, and Edwin until 1934. At that time little grain was being grown in the Grand Traverse region, and the mill was about to be closed because business was slow.

The mills last day were remembered by son, Edwin. Ed went to a dance in Suttons Bay that night. When he returned, he found that part of the concrete wall of the water box had given away, and the planking on which they had stood that afternoon was 100 yards out on the bay ice. “If it had happened during that day,” he said, “we’d both have been goners for sure.”

The mill stands empty now, but the dam on Belanger Pond lingers on, tranquil and serene. The mill is registered on the list of Michigan Historic Places, and is just a memory, just a ghost town. And as far as we know, it does not carry the ghost town curse.

Courtesy: “The California Report,” by Carly Severn, Jan 12, 2018; AHGOSATOWN, By Elizabeth Craker from the Omena Historical Society’s archives; “Omena, A Place In Time” by Amanda Holmes